Tue Oct 25, 2016

I didn’t quite expect an issue of Doom Patrol to appear so soon, but here we are. Possibly the single greatest comic run I own, by the author whose work(s) I try to follow more than any other (Grant Morrison). (As an aside, I had the help of a friend in completing this run some time ago, and I am reminded that I still need to pay her back for her help in doing so.)

The Doom Patrol, as characters, have always fascinated me in the way that the X-Men tend to for most readers. They’re outcasts who fight against the banality of the status quo and champion individuals and groups on the margins of society. Of course, the original Doom Patrol team managed to out-hero the X-Men by giving their lives for a small fishing village. And the characters stayed dead for some time! (This is unheard of in comics, unless you were Ben Parker or Bucky Barnes … at least until the early 2000s.)

So, having Grant Morrison provide his take on the Doom Patrol is/was positively awesome, especially since this take involves surrealism, dada, comics deconstructionism, and a fundamental plot-line later ripped off by M. Night Shyamalan for his movie Unbreakable.

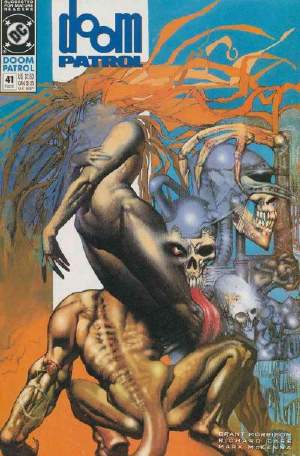

The cover to Doom Patrol 041, by Simon Bisley (I think? I feel pretty sure about this, since he loves to do hyper-detailed elbows), is suitable for the comic: there’s a naked, faceless woman (a character named Rhea, who appears within the issue) floating above a naked, muscular humanoid with a tail and visible spine nearly protruding through its skin. To the right of these figures are various skulls and skeletal limbs; at least one of the skulls appears to be screwed or bolted to some mechanical/industrial apparatus.

Doom Patrol issue 041

So, the issue begins in a typically cryptic Morrison way, with a woman visiting “one of the five” lost and found offices that are special in some way. They contain lost memories, confidences, innocence, etc. The woman visiting the office is looking for Flex Mentallo, a comic character lost since the 1950s. I love Flex Mentallo, so I’m stoked to see if he makes an appearance in this issue, although his “first appearance” doesn’t actually occur until the next issue.

Robotman is in his “spider legs” phase in this issue, which was another neat twist on the character—I liked this aesthetic more than his giant shoulder-pads during this run. I always appreciated Robotman for his sleek look; the shoulders scream ‘90s and it’s just not a great look. That said, I do appreciate that it’s a kind of expression of his efforts to find a personal style, since he’s basically a disembodied brain in a mobile tin can.

The plot of this issue is a climax to a multi-issue storyline. Here, the anathematicians face off against the agent of the kaleidoscope in a battle of potlatch (having had the concept introduced to them by the Negative Man) wherein they take turns destroying more and more important & valuable symbols of their ideologies.

Meanwhile, Robotman, on the advice of Rhea, plants a flower and a giant angel (in the form of a massive rock with three or more human faces on which sits a city) comes to life and is apparently named Balzizras. It had created a world devoid of creativity, being able to imagine only simple conflict between those warring ideologies. Now, the flower allows for free imagination: “The creator’s come down among you, not as a judge, but as a sort of imaginative energy. Pretty neat, huh?” When Robotman asks if it’s really an angel, Rhea replies: “Well, it’s either that or the psychic projection of a woman called Ilse Krauss who’s lying in a hospital bed in Bremen, dying of brain cancer. It’s hard to be sure.”

This is the kind of concept that I love reading about in comics. Morrison knows exactly how to tap into the part of my brain that drinks in the most incredible high-concept ideas spitballed in half-formed states, since they allow the reader the opportunity to imagine how the ideas might be realized. The conflict is resolved by heroes who are willing to consider completely absurd and seemingly unrelated solutions, and the payoffs are frequently not returns to the status quo but radical paradigm shifts in which the characters (and the reader, hopefully?) develop further via the enlightenment they’ve gained.

Pretty much every storyline in Morrison’s Doom Patrol run achieves this without disappointing; the same can be said of his JLA, Animal Man, All-Star Superman, and New X-Men runs (maybe not quite to this extent with New X-Men, perhaps). It’s this desire to use the superhero mythos as a way to promote internal philosophical development on the part of the reader that makes me appreciate Morrison’s writing. Sure, it’s interesting when superheroes are taken seriously (a la Watchmen), but it’s even more interesting to me when the concept of the superhero is taken philosophically and explored as a potential humanist value system (or at least the vehicle for one).

So, yeah. I love the Doom Patrol and I love this issue’s story as an awe-inspiring demonstration of superheroes through those characters.